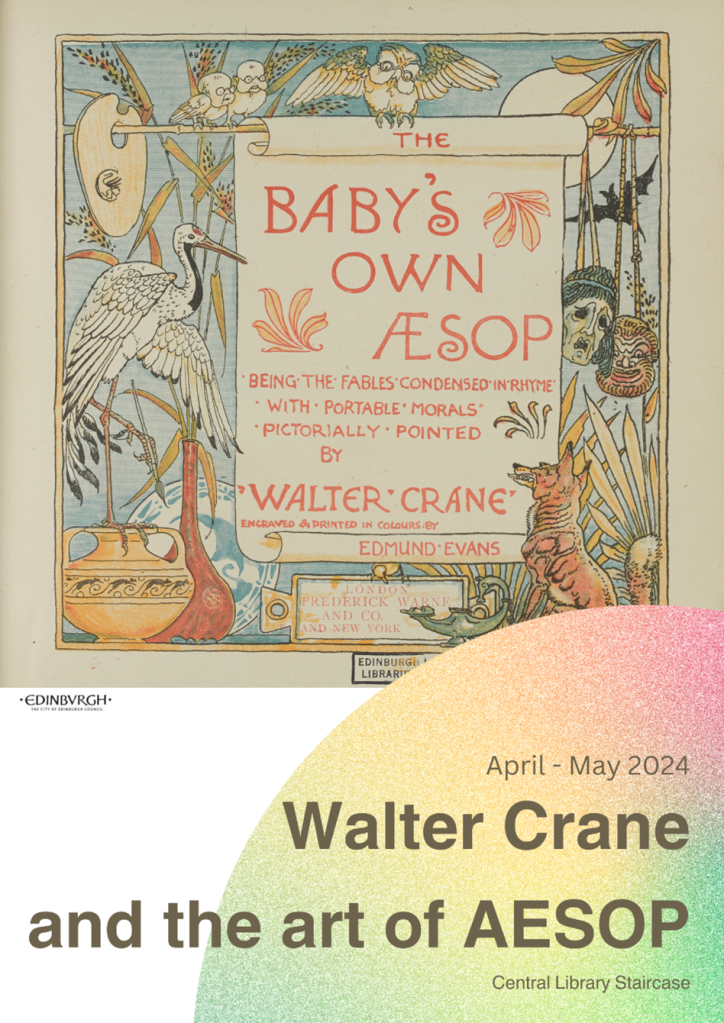

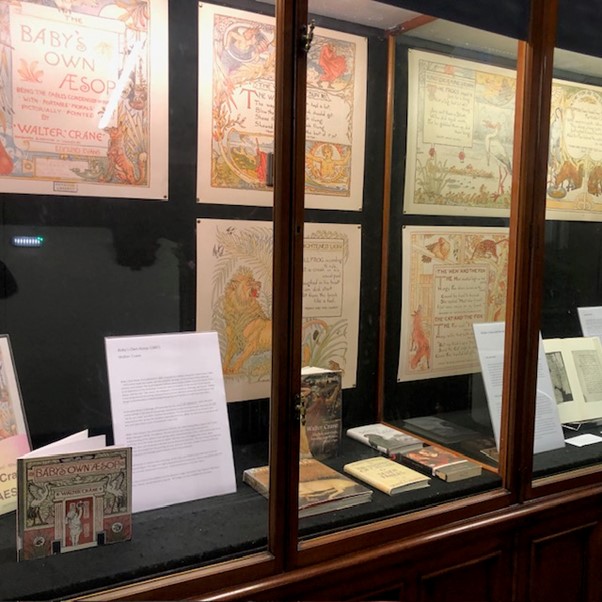

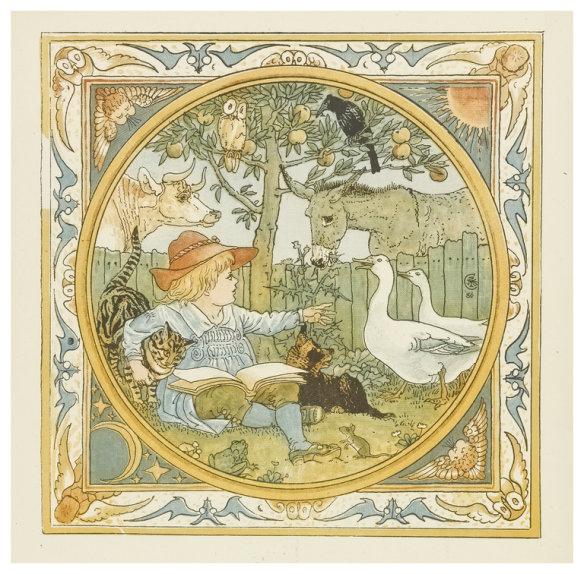

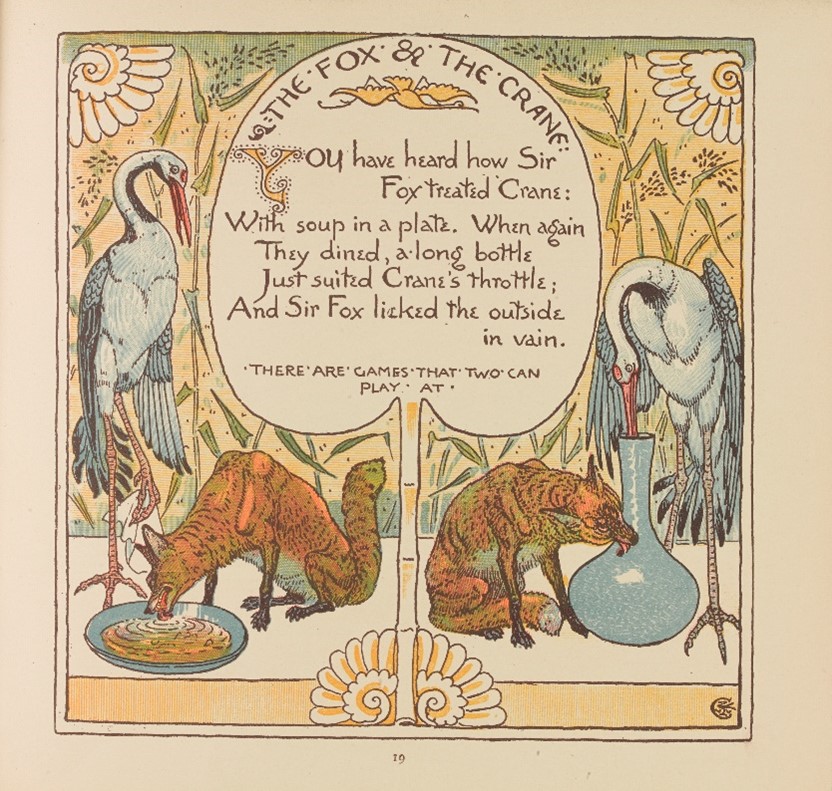

Throughout April and May in our staircase exhibition space at Central Library we are showcasing one of our special collections’ books, Baby’s Own Aesop, by Walter Crane (1845- 1915).

First published in 1887, it is a book for children which leads the reader, and the onlooker, through a series of beautifully elaborate pictures and rhymes. The wood-engraver William James Linton (Walter Crane first knew Linton as an apprentice in his workshop), wrote the verse in imitation of the ancient Greek fabulist Aesop, and the rest – the covers, the endpapers, the frontispiece, lettering, and layout – Walter Crane designed and the printer Edmund Evans printed. Behind it all was the belief that art and design could stimulate a child by being interesting and therefore it could help them learn.

As an artist Walter Crane was affiliated with the Arts and Crafts Movement, which elevated craftsmanship in the face of increasingly mechanised production techniques. Aestheticism and “art for art’s sake” are other common associations. The formal qualities of an artwork were important to him, as was his socialism, especially from the 1880s. His wish was to popularise the arts and make them a part of everybody’s daily lives.

You can also browse all the illustrated pages from Baby’s Own Aesop on our online image library, Capital Collections.

Who was Aesop?

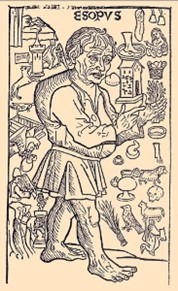

What we know about Aesop is murky at best. He belongs to the oral tradition of storytelling and he reportedly lived in Ancient Greece between 620 and 564 BCE. It is said that he may have been a slave, also that he was strikingly ugly, and that he was tongue-tied until the goddess Isis granted him the power of speech and storytelling prowess… Multiple versions of him exist and no original sources survive to tell us. As a storyteller he is as much a story himself as the stories he tells. The Greek historian Herodotus mentions him in the 5thc. BCE – and other ancient writers refer to him; Plato, Aristotle, Plutarch, and more. His name was well known, and yet we still know very little about him factually. He is very much a legendary figure, and has become the associative, encapsulating name for the animal fable in general.

What is a fable?

There is so much variety in what a fable is but broadly, it is a short, fictitious story, where everyday animals, objects, plants, or natural phenomena are the central protagonists. They are given thought and speech, and treated as if they are human. Fables are also usually thought of as having an element of morality to them, with religious, social or political themes; some kind of truth, and this reflects back onto the communities and time period in which they are told. For example, a fable is a bottom-up way of talking truth to power in a highly hierarchical society like Imperial Rome. Fables are very fluid texts and are used by different ideologies and for different agendas. Often, they are strange and contradictory, with many meanings.

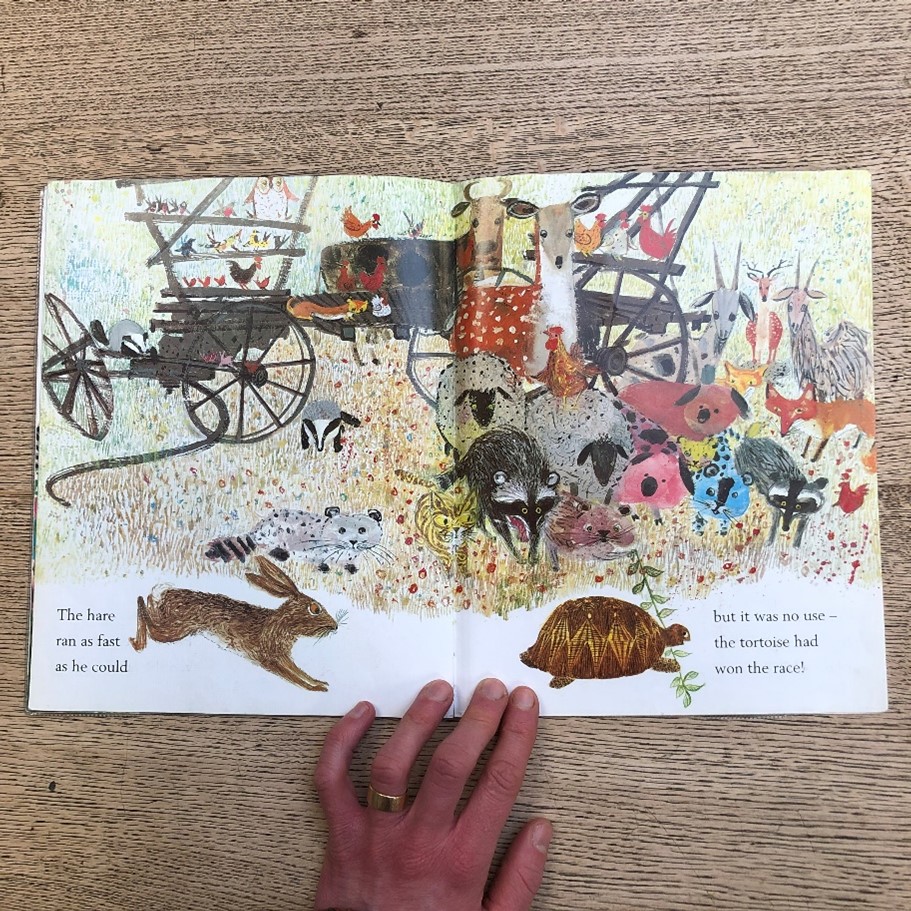

Over the centuries fables have been used for pedagogy as well as entertainment, and especially from the Renaissance onwards, they have been very much associated with children. A moral from the mouth of an animal is more persuasive somehow. Also, there’s something about using an animal as a character that can specify more in a narrative than using a human perhaps; using a fox to denote a cunning person tells us more than using a human for that same character.

What does being an animal say about being a human and human society? As we know from our own culture, the animal fable holds the means to discuss so much.

Origins and history

The animal fable tradition stretches back much further than Aesop’s Greece, and indeed fable stories have been found on Sumerian tablets from c.3000 BCE. They have grown out of the oral tradition; Aesop never wrote anything himself.

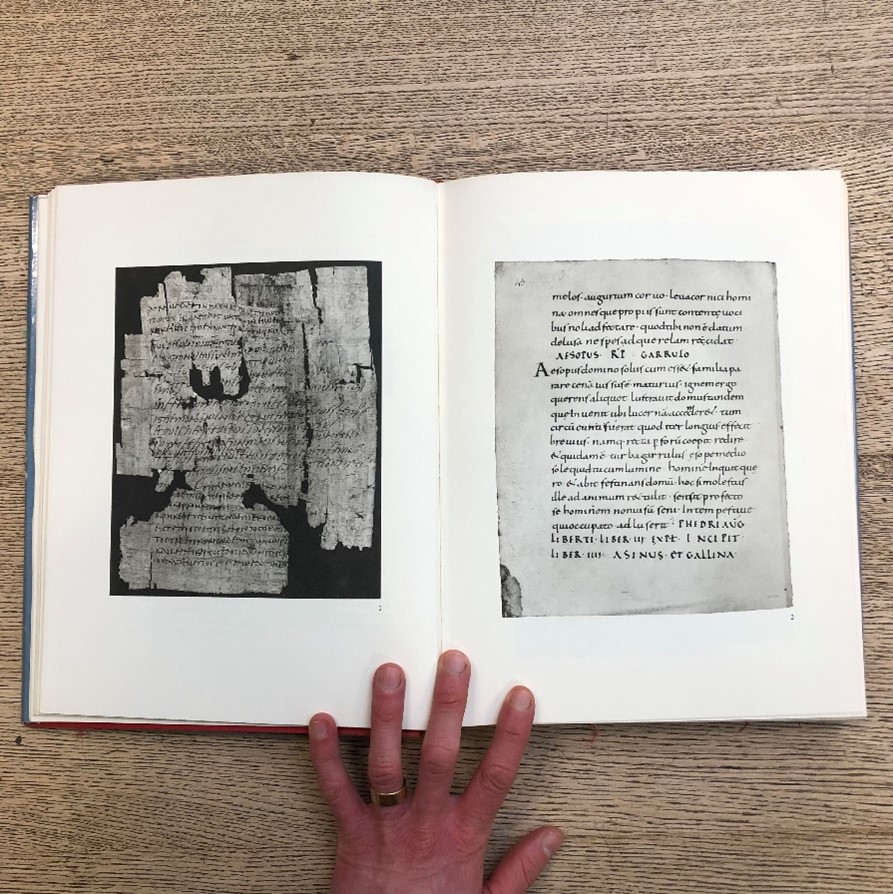

In the late 4th c. BCE Demetrius of Phalerum is credited with putting together the first collection of fables that we know about, but our oldest surviving manuscript that is a collection of fables dates from the 1stc. CE and was written by the Roman poet Phaedrus in Latin verse. In Greece, the poet Babrius wrote another collection in Greek verse – again this was a literary work.

Rhs. Fabularum Aesopiarum, Phaedrus.Latin, [Reims, France: 9th c.] M.906 [Codex Pithoeanus.]

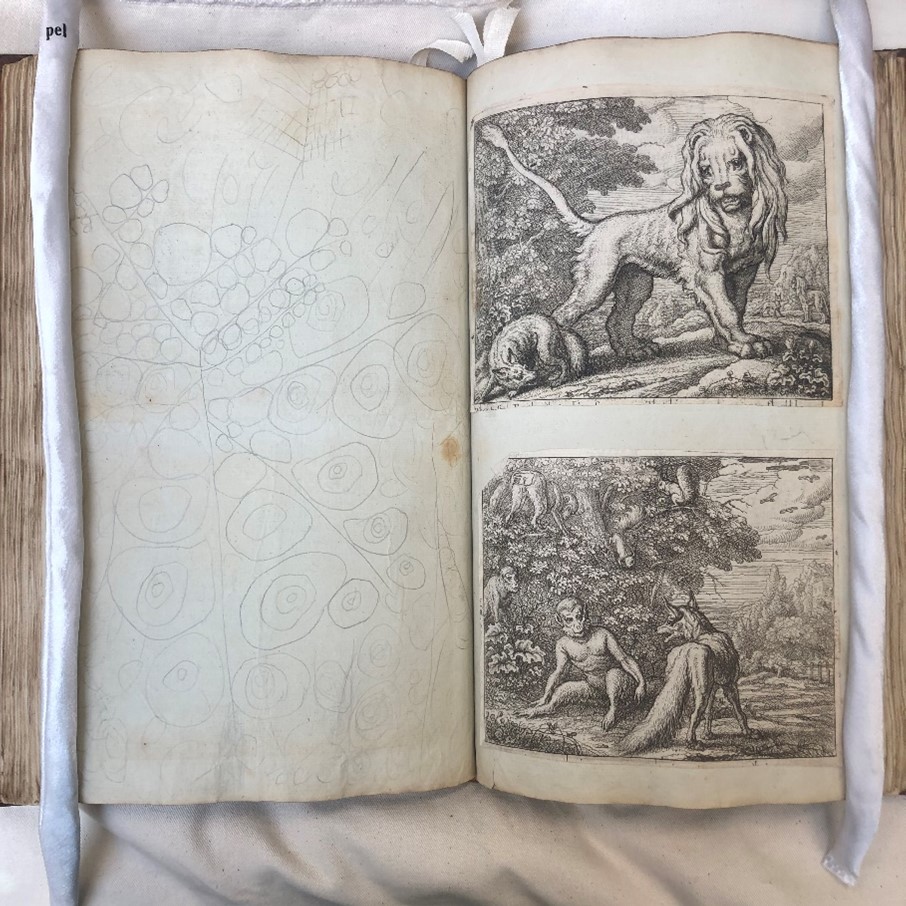

Images from Early Children’s Books and Their Illustration, text by Gerald Gottlieb, essay by J.H. Plumb. The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York; Oxford University Press, London; 1975.

In the European written tradition, the fables travelled over the centuries in both Greek and Latin – and around 1476 they were translated into German by the humanist writer and doctor, Heinrich Steinhöwel. From there they were translated into Italian, French, English (the Caxton edition from 1484), Czech, and Spanish. In the 16thc. Portuguese monks took Aesop to Japan; and in the 17thc. the fables were brought to China. They have spread into majority and minority languages all over the world.

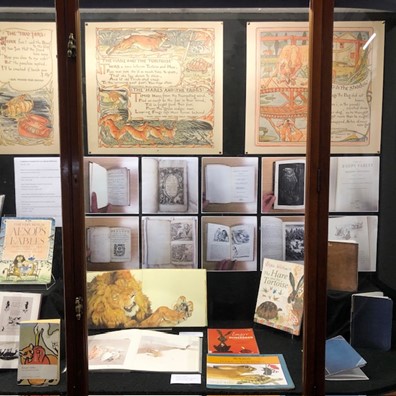

With the invention of moveable type in the 15th c. Aesop’s Fables were among the first books to be illustrated, and they have been so enduringly popular they can almost be read as a history of the printed book and a showcase of printmaking techniques.

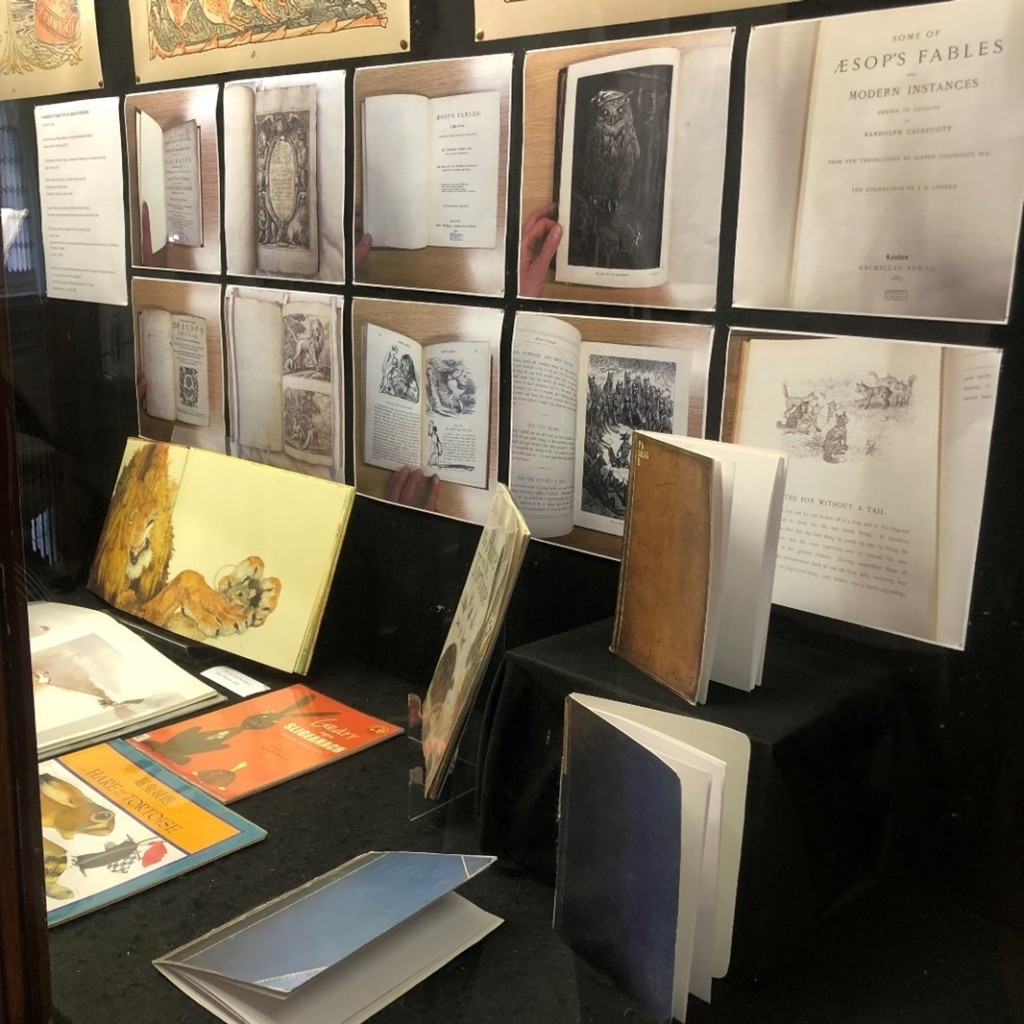

On display are examples of early woodcuts, and finer, more detailed copperplate etching – by Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder in the 16th c., and Wenceslaus Hollar and Francis Barlow in the 17th c. (most of Hollar’s etchings were based on drawings by the artist Franz Cleyn.)

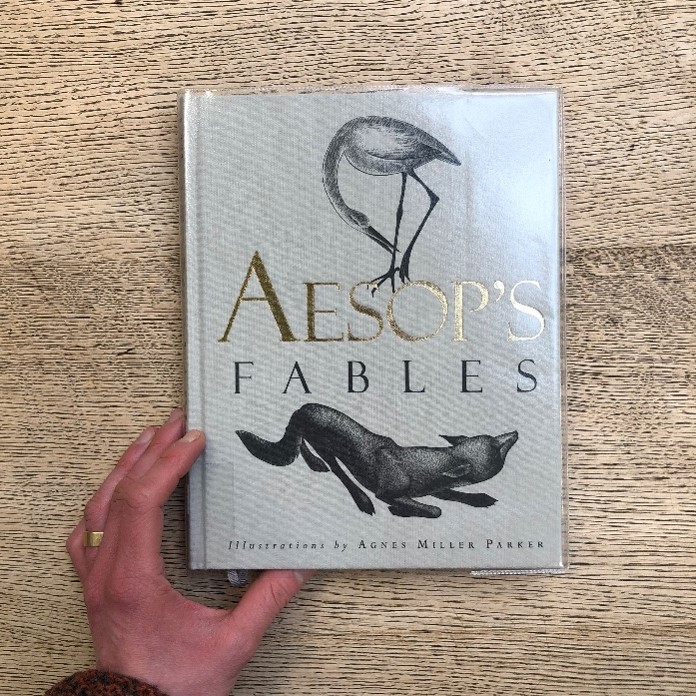

Other notable illustrators of Aesop’s Fables were John Tenniel (he was unhappy with the work and redrew some of the tales for a later revised edition), Randolph Caldecott, Ernest Griset, and Harrison Weir. Arthur Rackham published a collection of fables in 1912 with a new translation by V.S. Vernon Jones, and more recent examples from the wonderful world of children’s book illustration include Lisbeth Zwerger, Brian Wildsmith, Jerry Pinkney and Charlotte Voake.

Laura Gibbs, who translated the fables for the 2002 Oxford World Classics edition, also has a comprehensive web presence which includes selections from all major Greek and Latin sources.

Lastly, in our special collections we hold a number of important editions: including a 1676 Latin edition printed in Edinburgh by George Swinton; a 17th c. English translation with illustrations by Francis Barlow (1687); and an 1887 edition translated by George Fyler Townsend (a popular 19th c. translation) with Harrison Weir illustrations. Also copies in Greek and Italian; translations by Samuel Croxall and Sir Roger L’Estrange; some of the John Tenniel illustrations; and a beautiful Ernest Griset copy.

Please do come in and browse our many many books!