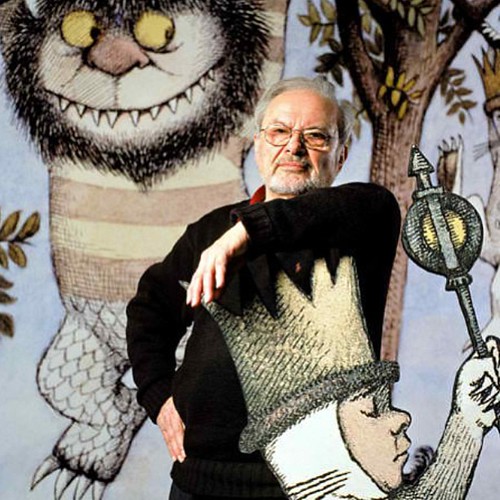

Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are was published in 1963 – a much loved, much lauded, very famous picture book. And as an illustrator, he has opened and generously filled the imaginations of little minds everywhere. Wild thing critters, with their big heads and short thick legs, judder through his books in hatchy ink, or graphite, and watercolour. He can draw a jitter perfectly, a heebie-jeebie in the trees; just let the rumpus begin.

What is less known about Maurice Sendak is that in the 1970s he began what he referred to as his second career, shifting away from illustrated books – very willingly – into the world of set and costume design. He found a release in the theatre, “I became the person I want to be”, he said of it, and the storyboards, watercolours, dioramas, preparatory sketches, props and costume studies, all the many things he made during this time, are a wonderful expression of just that. As with all great artists, he knew how to make his work distinctly his own.

When he died in 2012 he bequeathed a large amount of his work to the Morgan Library and Museum in Manhattan, and in 2019 they put on a show, Drawing the Curtain: Maurice Sendak’s Designs for Opera and Ballet. (The book is on order for the Art & Design Library, it’s a treat, and will be available for borrowing soon. In the meantime, do image search the designs and visit The Morgan’s website).

Mozart’s The Magic Flute

“I know that if there’s a purpose for life, it was for me to hear Mozart,” Maurice Sendak once said. And so when the director Frank Corsaro contacted him and asked if he might design the sets and costumes for The Magic Flute with Houston Grand Opera, Maurice Sendak was delighted – nervous because of his inexperience – but excited. (“You wanted a fresh, dumb designer and, God help you, you found one,” he wrote later.) Frank Corsaro had no idea of Maurice Sendak’s passion for Mozart; he’d been reading his illustrated edition of The Juniper Tree and Other Tales from Grimm (1973), and in terms of mood and tone, he thought Maurice Sendak would be a perfect fit for his new project.

First performed in 1791, The Magic Flute was Mozart’s last opera, and it has long been seen as a gift for the designer. It is the story of the fantastical adventurings of Tamino and the birdcatcher Papageno. Pamina, the daughter of the Queen of the Night, has been kidnapped by the ‘evil’ high priest Sarastro, and Tamino and Papageno are to rescue her. They are given magical musical instruments to help them; Papageno, bells, and Tamino, a magical flute, but on meeting Sarastro their quest isn’t quite as clear as they first thought.

Both Mozart and his librettist Emmanuel Schikaneder were freemasons, and this thread of enlightenment philosophy runs throughout the opera. Early masonic texts trace the ‘craft of masonry’ to Euclid in Egypt, and thus masonic imagery has always been wedded to Egypt. Corsaro and Sendak agreed they would set the opera in Mozart’s time. They would tell Mozart and Schikeneder’s story and explore these founding themes. They wouldn’t overturn, defamiliarise, or subvert; they would employ none of these sorts of approaches, approaches that an artist-turned-set-designer might readily employ. They were storytellers, historians; and Maurice Sendak set about his excavations into art history for imagery. He drew sphinxes, temples, pyramids, Horus figures, beds, hieroglyphs… Tut mania was in the air in the late 1970s as a major exhibition of Tutankhamun’s tomb was touring the country. It reached The Metropolitan Museum of Art in December 1978 – and whether Maurice Sendak saw it or not is unclear, but he was certainly looking at the objects when he was drawing his designs.

Maurice Sendak loved Mozart. He loved all music but he loved Mozart especially. As he drew he would always listen to music, and music and drawing shared a symbiotic relationship for him. He’d sit in front of the record player and reach out for what he felt would suit his drawing. He called it choosing a colour, and the colour had to be just right. In an article he wrote for the Sunday Herald Tribune called “The Shape of Music” (1964), he elaborated on this: how he conceives of his drawing as a musical process; how drawings must be animated, and how they must have a sense of music and dance – they cannot be glued to the page. The artists he most admires he thinks of in terms of their musicality; their artistry has an “authentic liveliness” as he calls it. He’d turn to books too, “but it is music that does most to open me up,” he said.

He also drew wonderful fantasy sketches of operas, even before he started to work on them, The Magic Flute being one of them. And just as he saw the work of the illustrator as illuminating a text, so too he saw set design as being in service to the music: “… your job is to make Mozart look even better, if that is even possible,” he wrote.

Listen to The Magic Flute on Naxos.

Watch performances of the opera, as well as documentaries, on Medici TV.

Watch a short video and take a look at some of Maurice Sendak’s designs on the Morgan Library & Museum website.

The article, “The Shape of Music”, is collected in Maurice Sendak’s book Caldecott & Co.: Notes on Books and Pictures, and is available for borrowing from the Art and Design Library when we reopen.

Prokofiev’s Love for Three Oranges

Prokofiev’s Love for Three Oranges is a commedia dell’arte fairy tale about a young prince, who is cursed by a witch and travels to faraway lands in search of three oranges, each of which contains a princess.

The tale was collected in Giambattista Basile’s Pentamerone, and in the 18th century, it inspired the playwright Carlo Gozzi to write L’amore delle tre melarance. Prokofiev based his opera on Gozzi’s play as well as a translation of the play by the Russian director Vsevolod Meyerhold.

It was The Morgan Library and Museum’s Tiepolo drawings, and in particular Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo’s Punchinello sketches, that inspired him. He wrote to Frank Corsaro: “It is an odd matter indeed, this almost magical union that occurs between stealer and stealee; it is as though I know what I want but can see it only inside (in this case) a Tiepolo drawing and then I can draw it out and make it quite properly my own.”

They produced the opera for Glyndebourne, the first Americans to be invited to do so, debuting there in May 1982.

In 2013, New York City Opera filed for bankruptcy and many sets and costumes, Maurice Sendak’s among them, were auctioned off. Some photographs are available on the Cotsen Children’s Library’s blog and on the R. Michelson Galleries website (have a look at, among other things, the peeing fountains, gondolas, throne coverings, a dragon in the clouds, and many many hats…)

Listen to Prokofiev’s Love for Three Oranges on Naxos.

Watch the opera on Medici TV.

Browse the Tiepolo collection online at The Morgan Library and Museum.

Janáček’s Cunning Little Vixen

Janáček’s Cunning Little Vixen is another opera Maurice Sendak and Frank Corsaro collaborated on for New York City Opera, premiering in April 1981. It tells the story of a feisty young vixen who is captured by a forester but later escapes. She then marries, has cubs, and dies at the hands of a poacher. Revisiting the place where he first caught the vixen, the forester encounters a baby generation of forest animals and is reminded of the cyclical beauty of nature.

Maurice Sendak chose to unapologetically anthropomorphise his animals. The characters he designs are musicians, actors and actresses, dressed up – as a fox or a badger or a frog. He designs the artifice. It is a fun, playful, joyful thing this artifice.

Listen to Janáček’s Cunning Little Vixen on Naxos.

Watch the opera on Medici TV.

Do just image search the designs – visit the R. Michelson Galleries website to see 3 sets of chicken feet, frog feet, weasel feet, headpieces for weasels, woodpeckers and ants…

Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker

In 1983 Maurice Sendak designed the sets and costumes for Pacific Northwest Ballet’s The Nutcracker. It was his first without Frank Corsaro and he was proud to have achieved it on his own. The original ballet is “about a little girl,” he said in an interview with Marcia Alvar, and “a dream she has… all these adventures occur… [the wooden nutcracker toy comes alive. The evil mouse king declares war and is defeated. The young prince carries her away to a magical garden kingdom in the clouds]… and then at the end… a whole bunch of grown-ups dance at her party. No kid would want that.” Maurice Sendak was unenthused by the project at first, and prickly for being pigeonholed always as an illustrator of kiddies’ tales. And so he made changes, he returned to E.T.A. Hoffman’s story and darkened it up. Marie – Clara, in Sendak’s version – becomes a young woman, and instead of travelling to a land of sweets, she arrives at a seraglio. “A throbbing, sexually alert little story,” he called it.

In 1984 a book was released, and in 1986, the film version.

Nutcracker: The Motion Picture with designs by Sendak is available to watch on Amazon Prime (for a small fee unfortunately, but it’s available).

Listen to Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker on Naxos.

Watch the ballet on Medici TV.

Articles of interest (great pics included):

A New York Times review of the exhibition.

A Smithsonian Magazine review of the show.

A Brainpickings article on Maurice Sendak and “The Shape of Music”.