When you think of Edinburgh 100 years ago, do you imagine bohemian gatherings of artists and writers in a European-style salon?

To mark LGBTQ+ History Month 2024, Nicky from the Art and Design Library team shares an intriguing journey through Edinburgh history that she stumbled upon thanks to a series of serendipitous events involving books from the Art and Design and Edinburgh and Scottish collections. A small display of books accompanying this blog post can be found in the glass cabinet outside the Art and Design library.

Back in 2019 in a previous job, I first came across the book Rainbow City: Stories from Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Edinburgh. It contains stories and histories gathered during Remember When, a collaborative, community-history project organised by the City of Edinburgh Council and The Living Memory Association in 2004–2006. The book tells how, in 1972, while ‘homosexual acts’ were still illegal in Scotland, the University of Edinburgh’s Catholic Chaplaincy basement café, the Cobweb at 23–24 George Square, became “with the support of the then chaplain, Anthony Ross”, “the meeting place for Scotland’s first official gay and lesbian rights organisation, the Scottish Minorities Group” (1). The book also briefly mentions a John Gray and a Marc-André Raffalovich who “made new lives in Edinburgh after [Oscar] Wilde’s imprisonment for sodomy in 1895” (2). However, these names meant nothing to me at the time.

Fast forward to 2023 and the Art and Design Library, and I was processing a book requested by a reader, Caroline Maclean’s Circles and Squares: The Lives and Art of the Hampstead Modernists. Not knowing exactly who the Hampstead Modernists were, I flicked through the pages. The Hampstead Modernists included sculptors Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth and her husband John Skeaping; painters Ben and Winifred Nicholson and Paul Nash; Bauhaus founder architect Walter Gropius who first sought refuge from Nazi Germany in England; and critic and poet, Herbert Read (all of whom you can find out about in the Art and Design Library).

This book contains a chapter on Read (1893–1968) and his second wife, viola player, Margaret Ludwig (1905–96), known as Ludo. And because of a distant family connection to Margaret Ludwig, I skim-read that whole chapter, and discovered that she and Read had first met at a Sunday lunch party hosted by Marc-André Raffalovich and Father John Gray at Raffalovich’s house in Whitehouse Terrace (3), while Read was the first professor of Art History at the University of Edinburgh (1931–33) and Ludwig was teaching in the University’s music department. Their subsequent affair caused scandal in the city. This story is confirmed in more detail in James King’s The Last Modern: A Life of Herbert Read (4).

By 2023, I hadn’t remembered my previous encounter with the names Raffalovich and Gray, but the descriptions in these two books of their lives in London and friendships with other men in Oscar Wilde’s circle, and close friendship in Edinburgh, sent me back to Rainbow City where I rediscovered their names. By this time, my curiosity was well and truly sparked, and I wanted to find out more and whether there were any books about Raffalovich and/or Gray in our library catalogue. It turns out that there are books, at least eight about Raffalovich and Gray, and of Gray’s prose and poetry.

But who exactly were Raffalovich and Gray and what were their Sunday lunch parties in Whitehouse Terrace all about?

Marc-André Raffalovich (1864–1934) and John Henry Gray (1866–1934) were both incomers to Edinburgh, arriving in the early years of the twentieth century.

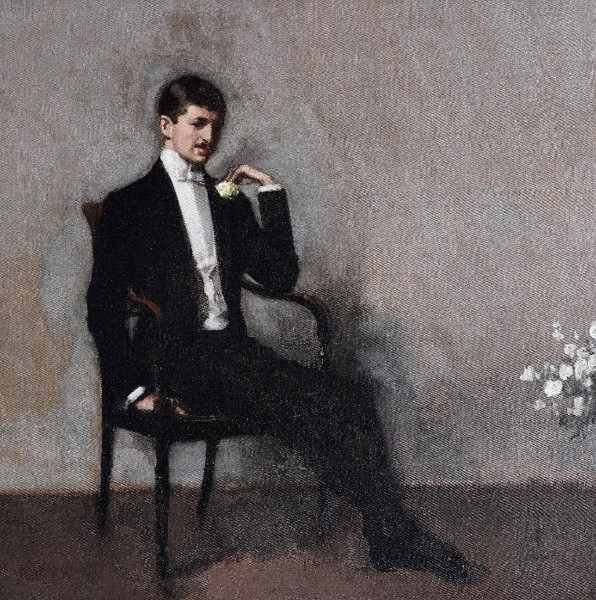

portrait by Sydney Starr (1857-1925), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Raffalovich was born in Paris, youngest of the three children of Herman, who became a successful banker, and Marie, whose salon attracted famous creative names of the day such as actress, Sarah Bernhardt, and writer, Colette. Herman and Marie were also philanthropists. The Jewish Raffalovich family had emigrated from Odessa in the Russian Empire (today in Ukraine) to Paris the year before Marc-André’s birth rather than convert to Christianity. Aged 18, Marc-André himself moved on, with his former governess Florence Gribell (1842–1930), to England with the intention of studying at Oxford. However, he ultimately settled in London and became part of the literary, artistic homosocial and homosexual circles including Oscar Wilde and artist Aubrey Beardsley among others and wrote poetry and essays. It was here that he and Gray met (5).

Gray was the eldest of the nine children of John, a carpenter at Woolwich Arsenal, and Hannah, who converted to Catholicism in the 1890s. Gray left school in south-east London aged 13 for an apprenticeship at the Arsenal and later moved on to its drawing office, all the while continuing his own learning in literature, French and German. This led to work as a civil servant and in the library at the Foreign Office. By late 1880s, Gray was writing and translating poetry, his own poems appearing in literary magazines, and he was a regular at literary clubs where he became friends with contemporary writers and artists including Wilde for whom Gray is widely believed to have inspired the character Dorian Gray (6).

During the 1890s, Raffalovich and Gray continued to write and together penned and produced a play, and Raffalovich wrote a defence of alternative sexualities, Uranisme et Unisexualité; ‘uranism’ was the word used medically and otherwise in various European languages at the time to describe male homosexuality, and both men were increasingly interested and involved in Catholicism. In 1898, Gray moved to Rome to train as a Catholic priest at the Scots’ College in Rome and was ordained there in 1901. A year later he had arrived in Edinburgh as curate for the impoverished city-centre parish of St Patrick’s, Cowgate. Meanwhile, Raffalovich had visited his friend in Rome and had also converted to Catholicism. He became a lay brother of the Dominican order (Blackfriars) and followed Gray to Edinburgh in 1905, where he bought no. 9 Whitehouse Terrace, with Florence Gribell as his dedicated housekeeper. There, he quickly developed a salon after his mother’s model in Paris (7).

From 1905 until the early 1930s, Raffalovich, Gray and Miss Gribell co-hosted Sunday lunches and Tuesday evening dinners at no. 9 Whitehouse Terrace. Attendees and atmosphere are recollected by poet and regular visitor, Margaret Sackville (herself another cause of local and national scandal due to her long-term liaison with widowed prime minister Ramsay Macdonald). In her contribution to Two Friends, ‘At Whitehouse Terrace’, published in 1963, she noted the presence of: Walter Sickert (1860–1942), painter; Gordon Bottomley (1874–1948), poet; Max Beerbohm (1872–1956), writer and caricaturist; Charles Saroléa (1872–1956), lecturer from 1894 and professor of French at the University of Edinburgh from 1918 to 1931, Belgian consul in Edinburgh and book collector; Compton Mackenzie (1883–1972), writer of fiction, histories and biographies; James Pittendrigh McGillvray (1856–1938) sculptor, poet, painter, printmaker and photographer; Peter Anson (1889–1975) writer and Catholic convert; and Father Hugh Benson (1871–1914) writer and Catholic priest (brother of E. F. Benson, author of the Mapp and Lucia stories); as well as numerous international visitors (8). She continued by describing the society and atmosphere at Whitehouse Terrace and Raffalovich’s hospitality:

“These and sundry other artists, writers, professors, some famous, some forgotten, who enjoyed that friendly atmosphere of sophisticated simplicity, if I may so call It, form a Gallery notable in any city, but in Eastwind-swept Edinburgh certainly unique. André’s gifts as a discerning host were evident in the care with which he chose his guests. He shrank from anything, whether human or inanimate, which was out of scale with his own preferred dimensions. This sensitive selection suggested his careful arrangement of the small flowers he loved so well and displayed with true affection to a responsive guest. … This happy appreciation of exquisite detail gave his hospitality the quality of a work of art: art saved from mere aestheticism by the human warmth which inspired his generous friendships. Many must still remember these unique gatherings with lasting gratitude” (9).

The nature of Raffalovich and Gray’s relationship over the years is not clear, and it would be wrong to apply our present-day understandings of romantic, sexual and platonic relationships to their lifelong committed and close friendship. Nevertheless, during Raffalovich’s first years in Edinburgh, his generosity as a patron and friend to Gray was demonstrated in his significant financial contribution to the construction of St Peter the Apostle Church, Falcon Avenue, Morningside. Gray was its first parish priest, from 1906 until his death. The church was designed by celebrated Edinburgh Arts and Crafts architect, Robert Lorimer (1864–1929) in a rural-Italian style, perhaps a reminder of churches seen by Gray and Raffalovich in the countryside around Rome (10). The church and presbytery (priest’s house) were constructed and fitted out between 1906 and 1927 and included sculpture and stained glass by frequent Lorimer collaborators, Alice and Morris Meredith Williams, who became friends with Father Gray (11). The community at St Peter’s today has compiled fascinating and detailed resources about the history and art of the church.

The public expression of Raffalovich and Gray’s friendship represented by St Peter’s Church brought, I thought, my discoveries to a close. However, just last month, I opened a book newly arrived in the Art and Design Library, Andrew McPherson’s William Gillies: Modernism and Nation in British Art accompanying the recent exhibition at the Royal Scottish Academy. In it, I spotted a chapter titled ‘Bohemian Edinburgh’ and the names Raffalovich and Gray jumped out. Of the Whitehouse Terrace salon, McPherson writes that “[i]ts axis of refinement, Catholicism and homosexual apology attracted a variety of minority interests and tastes, and also scores of young men of various, and sometimes insecure, sexual orientation.” Raffalovich and Gray’s circle

“included many of Gillies’ friends, colleagues, and students. Among them were Willy and Denis, the sons of S. J. Peploe and cousins to Margery Porter, Harry, the son of Henry Lintott, who had taught Gillies, Hew Lorimer, a Catholic convert and son of Robert Lorimer, architect of the National War memorial, Henry Harvey Wood and from an older generation, two of Gillies’ ECA Principals, Morley Fletcher, and Hubert Wellington, both of whom were again Catholic” (12).

Finally, for now, or at least until another book pops up, the contemporary significance and impact of the Whitehouse Terrace Sunday lunch and Tuesday dinner parties are neatly summed up by McPherson:

“For thirty years, the Raffalovich salon was the centre of high cultural life in Edinburgh and a node in the cultural life in Britain, with links to the highest levels of government and society, the elite colleges of Oxford and Cambridge, and two generations of Bloomsbury artists, writers, critics, bibliophiles, and publishers. It was also a perennial subject of Edinburgh gossip that found in the ambivalent celebrity of its habitués a confirmation of the equation, common to other capitals in Europe, of modernism in the arts with decadence in private life. Intellectual Edinburgh loved it.” (13).

Notes

- Galford and Wilson, p. 136.

- Galford and Wilson, p. 16 and p. 121.

- Maclean, p. 126.

- King, pp. 101–105.

- Sewell, 1963, p. 7f; University of Manchester Library Special Collections record for Raffalovich.

- Sewell, 1963, p. 7f; University of Manchester Library Special Collections record for Gray.

- Sewell, 1963, p. 7f; University of Manchester Library Special Collections records for Raffalovich and Gray.

- Sackville, p. 142; Wikipedia entries; University of Edinburgh archives record of Saroléa.

- Sackville, p. 143.

- Sewell, 1963.

- Sewell, 1968.

- McPherson, pp. 44–45.

- McPherson, pp. 44–45.

Books mentioned in this blog post

Galford, Ellen, and Wilson, Ken. (2006) Rainbow City: Stories from Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Edinburgh. Edinburgh: Word Power Books. (Edinburgh and Scottish, HQ 76.3)

King, James. (1990) The Last Modern: A Life of Herbert Read. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. (Art and Design store, N 8375 R28)

Maclean, Caroline. (2020) Circles and Squares: The Lives and Art of the Hampstead Modernists. London Bloomsbury. (Art and Design, N 6768.5.M63)

McPherson, Andrew. (2023) William Gillies: Modernism and Nation in British Art. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Savage, Peter. (1980) Lorimer and the Edinburgh craft designers. Edinburgh: Harris. (Art and Design, NA 997.L87)

Sewell, Brocard. (1963) Two friends: John Gray & André Raffalovich, Aylesford: Saint Albert’s Press. (Edinburgh and Scottish, BR 1844.9.G77)

Sewell, Brocard. (1968) Footnote to the Nineties: a memoir of John Gray and André Raffalovich, London: Cecil and Amelia Woolf. (Edinburgh and Scottish store, BR 1844.9.G77)

Sewell, Brocard. (1983) In the Dorian mode: a life of John Gray 1866–1934, Padstow: Tabb House. (Edinburgh and Scottish, BR 1844.9.G77)

Find out more in archive collections

More information about Raffalovich and Gray can be found in letters and papers deposited over the road from Central Library in the National Library of Scotland manuscript collections, search at https://manuscripts.nls.uk/, and in the University of Manchester John Rylands Library Special Collections LGBTQ+ collections.